Coaching to Good Value Content. Understanding our customers takes creativity and experience. As value coaches, we facilitate our team’s deeper customer understanding not by handing them answers, but by prompting them to ask good questions. Previously, we drew parallels between coaching soccer in the three phases of the game and coaching commercial teams in the three stages of value management and value selling. Quantifying value is like playing midfield. Designing Value Propositions requires the skills of a good back or keeper. Teams selling value need to be effective strikers.

So far, in this series on coaching midfielders to quantify value, we have reviewed how to help teams frame the discussion and how to focus their mindset on customer-centric differentiation. Starting with a clear framework of our offering, our customer, our reference alternative, and customer units, we arrive at the point of quantifying value based on our identified differentiated features translated into differentiated benefits.

To dollarize or euro-ize the value we create, we need to formulate hypotheses about the impact our offering has on our customer’s business. In this blog, we focus on how to quantify financial value.

Quantify and Dollarize Value[1]. We start with a midfielder’s view of the field based on differentiated features, differentiated benefits, and qualitative value drivers. We have identified ways our offering is better from our customer’s perspective. To quantify our added value, we need to connect our offering to our customer’s business. How does our offering make money for our customer? What are our offering’s benefits worth? Do we have any hypotheses, anecdotes, or data about how much better our offering is?

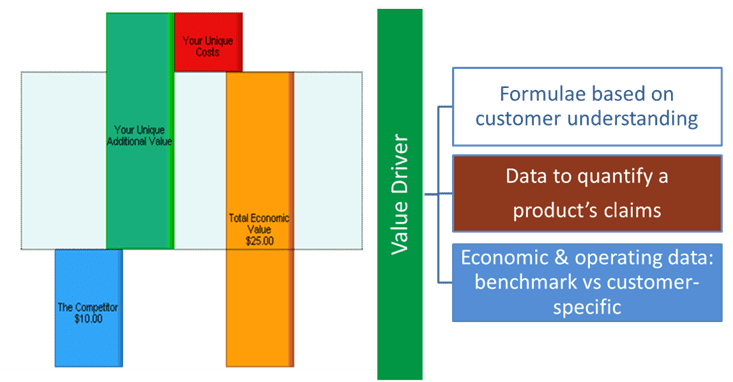

There are three elements of a value driver:

- formulae based on how we understand the customer and what our offering does for them,

- data that quantify the claims we make for our offering,

- background economic and specific customer operating data.

Sources of Value. We drive differentiated value through some combination of cost reductions and revenue increases. To dollarize them, we need to identify customer business parameters that our differentiation will affect and come up with plausible, quantitative estimates of our impact. With good hypotheses, we can ask good questions, tapping internal knowledge, outside experts, and friendly customers.

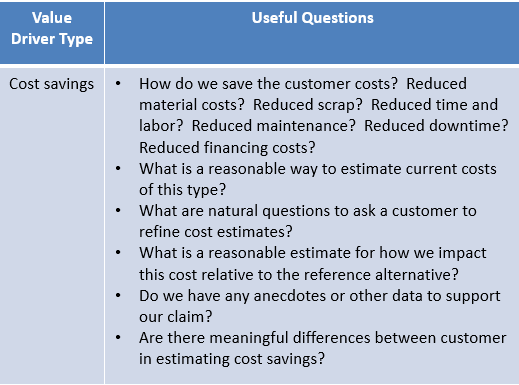

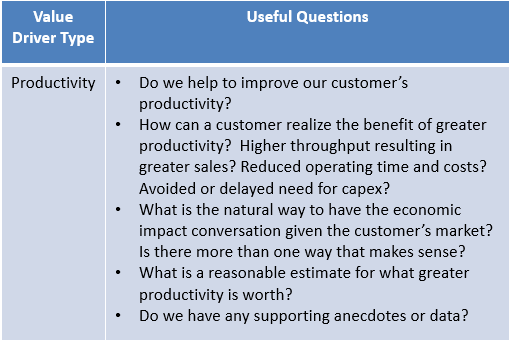

Good questions generally vary with the type of value driver:

-

- Some value drivers provide direct savings in current costs. When the reduction is measurable and validated, and when the current cost is well-identified, these cost savings have the potential for capturing a higher percentage of value in the price.

-

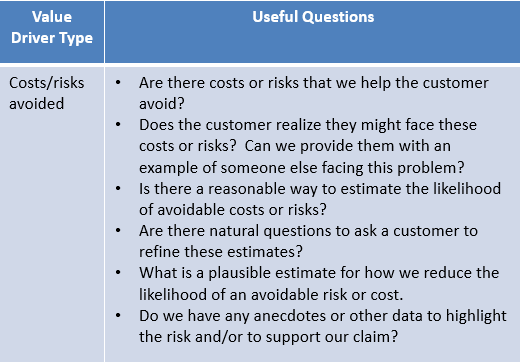

- Other value drivers result in costs or risks avoided. These costs and risks are sometimes less directly observed and may take more inventive inquiry. Some customers may not realize they face the underlying issue or that the cost or risk is significant. Some stakeholders may not see these costs or risks as their problem.

-

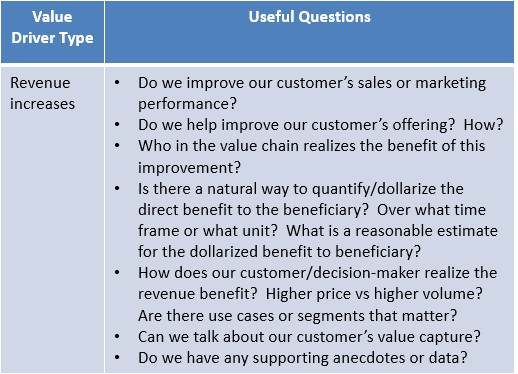

- Our differentiation may increase revenues for our customers by way of higher prices or greater sales volumes. Sometimes our differentiation directly improves our customer’s commercial performance, but revenue increases often arise from benefits for our customer’s customer. Thinking about the value chain and how we capture value from downstream beneficiaries is often part of estimating revenue value drivers.

- Our differentiation may result in productivity improvements, where there are differences among customers in how they realize the economic value of those improvements. Some customers obtain the benefit of greater productivity in operating cost savings. Others may be able to sell their greater production, realizing the value of enhanced productivity through revenues. Still, others may be able to avoid or delay capital expenditures as a result of greater throughput.

Let’s consider good coaching questions for each type of value driver.

-

Cost savings. In thinking through how our offering impacts the customer’s business process, we start by looking for direct cost savings. Do we reduce their material costs, their scrap rates, or their time and labor? Do we reduce their maintenance, their downtime, their inventories, or their financing costs?

Cost savings. In thinking through how our offering impacts the customer’s business process, we start by looking for direct cost savings. Do we reduce their material costs, their scrap rates, or their time and labor? Do we reduce their maintenance, their downtime, their inventories, or their financing costs?

Based on identified costs we save, we need a reasonable way to estimate a customer’s current costs or their costs with a competitor. Usually, this means identifying a few key metrics in their operating, sales, or administrative processes that relate to their scale. We can then start with normal percentages of those scale variables observable in other similar businesses, taking into account cost parameters, to arrive at a baseline cost.

There are many simple ways to estimate costs: marketing spend as a percentage of revenue times revenue, weight-based scrap costs times scrap rates applied to production volumes, the time to perform competing tests multiplied by the labor rate multiplied by the number of tests, original capital cost times maintenance expense as a percentage of capital cost or maintenance personnel times fully loaded labor rates. Googling to find benchmark data and typical percentages is often a great start. Our colleagues with experience in a customer’s business usually have a good sense of what is reasonable. Looking at a typical customer’s financial reports can fill out the picture. As we quantify these costs, it is important to be clear about units: per year, per part produced. As we refine these cost estimates, we need to come up with a few well-defined questions we can ask a customer or an expert on our team. Coaches prompt teams with ideas of where to look, who to talk to, simple ways to do the math, and the right questions to ask.

Having estimated costs with a reference alternative, we need to assess our offering’s likely impact on these costs. How long does it take to perform our new test? How much do we reduce inventory? By automating a manual process, how much time do we save? Often these estimates are based on observations by our development team or interviews with alpha or beta customers. Frequently we start with plausible hypotheses. Stress-testing the plausibility of these estimates is a helpful immediate checkpoint, knowing that we need to test them and gather more data later. Good coaches prompt teams to think through their collective experience, to get to hypotheses quickly, identify follow-up, and move on.

Documenting supporting sources, including links and references, is a habit coaches should encourage. Keeping track of qualitative and quantitative differences between customer types, as they are identified, helps to initiate value-based segmentation. Identifying actions and follow-ups is part of any good process. But we need to encourage teams to be practical in how they prioritize follow-up. What will we learn from further interviews? What is our likely return on time spent (ROTS)? When does the perfect become the enemy of the good? What is our deadline for getting to the first version?

Costs and risks avoided. Some costs avoided are clear enough and hard to distinguish from direct cost savings, e.g. development costs avoided or reduced compliance costs. Some costs or risks are less straightforward and require more creativity to quantify, e.g. reduced regulatory risk, reduced risk of a breach, or avoided future investment. Some customers may have taken steps to avoid these risks or costs, perhaps by setting up processes or by purchasing insurance. Other customers or stakeholders may not realize that these costs or risks exist. Or they may not start with a sense of their importance. Coming up with examples of bad outcomes is helpful, even if the magnitude of large risks or costs is not quantifiable with precision.

Costs and risks avoided. Some costs avoided are clear enough and hard to distinguish from direct cost savings, e.g. development costs avoided or reduced compliance costs. Some costs or risks are less straightforward and require more creativity to quantify, e.g. reduced regulatory risk, reduced risk of a breach, or avoided future investment. Some customers may have taken steps to avoid these risks or costs, perhaps by setting up processes or by purchasing insurance. Other customers or stakeholders may not realize that these costs or risks exist. Or they may not start with a sense of their importance. Coming up with examples of bad outcomes is helpful, even if the magnitude of large risks or costs is not quantifiable with precision.

The potential events we help avoid are often important as intangible or emotional value drivers. Whether and how they resonate will differ by customer. We need to start by painting a qualitative picture of what this cost or risk might mean, including potential losses. Catastrophic events experienced by others, e.g. major litigation or data breaches, are not just part of our messaging, but help to quantify the value of costs avoided and risks reduced. Visualizing an investment that can be deferred helps to estimate customer costs that can be postponed, as we think about how our solution lengthens equipment life cycles.

Then we need to estimate costs avoided. A standard approach to risk value drivers is to estimate a reasonable probability of an event, approximate the cost if the event occurs, and calculate the expected cost. For risks that result in regular events, like warranty claims, there are usually industry benchmarks or anecdotal information based on other customers that can be uncovered. Starting with hypotheses and asking questions is a good way to refine these estimates. For catastrophic events, probabilities are often small and more subjective. For these risks avoided, the potential cost of an event is usually large enough that starting with a low likelihood is a natural way to have a meaningful customer conversation. “Even if the likelihood of a regulatory shutdown is only one in a thousand…,” the expected cost is a value that is significant to many customers that can help a buyer justify a purchase.

For insurable risks, where the main damages may be covered, the costs of dealing with an incident are worth highlighting as a pain point for decision-makers. Management time, hassle, and distraction are inevitable. Not all insurance claims result in full recovery and not all customers are adequately insured, so having some notion of the outright potential loss from a catastrophic event is relevant even for the insured.

To get to the value driver, we need some assessment of our impact on the risk or cost. If our maintenance program has increased the life of an asset for another customer by two years, illustrating how we did it and highlighting the result bolsters the case for our claim. Showing a reduction in error rates for another customer, or providing a beta customer quote about meaningful improvements, helps to defend a plausible estimate of how much we reduce risk. As before, when we don’t have measured results to support our claim, starting with a credible assertion becomes the basis for customer conversations that will eventually result in anecdotes or outcomes data.

Good coaches help teams overcome their reluctance to estimate the impact of our offering by helping them realize that we have to start somewhere. Otherwise, we will never uncover the customer information and anecdotal evidence to support a stronger claim.

Revenue increases. Basing our value analysis only on the total cost of ownership tends to overlook revenue value drivers. Asking questions about revenue is important. Do we help our customer’s sales or marketing team perform better? Does our offering improve our customer’s offering? If our offering measurably improves our customer’s offering, who in the value chain realizes the benefit of this improvement?

Revenue increases. Basing our value analysis only on the total cost of ownership tends to overlook revenue value drivers. Asking questions about revenue is important. Do we help our customer’s sales or marketing team perform better? Does our offering improve our customer’s offering? If our offering measurably improves our customer’s offering, who in the value chain realizes the benefit of this improvement?

Improvements in our customer’s marketing or sales processes can be dollarized by understanding how their funnel or pipeline metrics contribute to total revenue and by assessing how we improve those metrics. Our offering improves their revenues directly by enhancing their commercial performance.

When we improve the quality of our customer’s offering, we should quantify and dollarize the value of that improvement to the beneficiary, regardless of who realizes the value. If our customer’s customer realizes value, we want our customer to communicate that value to their customer and we want to target our marketing toward audiences for whom our differentiated value is meaningful. Different beneficiaries sometimes benefit in different ways. Value-based segmentation is important both for us and for our customer selling our relabeled, reformulated, or transformed products down the value chain. A vertically integrated customer may realize value directly. When we sell into a supply chain of distinct businesses, we have the opportunity to capture less direct value based on a dollarized value obtained by an end user.

Revenues increase in only two ways, by increasing volumes or by increasing prices. Even if a better offering potentially increases both, it generally makes sense to focus either on prices or on volumes. If our customer is a small players in a competitive market, they are more likely to realize the value of quality improvements through greater market share and increased volumes. If our customer has market power selling differentiated products, they are more likely to charge higher prices for a better product, a circumstance where we might consider an exclusive contract. Partnering with them exclusively may help to increase their effectiveness in realizing greater revenues from higher prices.

When our value driver is based on our buyer obtaining a higher price, we probably want to have conversations with our direct customer about how they capture some of the quantified value their buyers realize, supporting them with a useful Value Proposition. In a collaborative partnership, we may also want to have explicit conversations with our customer about how we share value. Good coaches help teams think through alternative approaches to value realization as well as the segmentation that value chains often create.

Productivity improvements. Our offering may increase our customer’s productivity. The way our customer realizes the value may be simple. In agriculture, an increase in corn yields directly delivers higher revenues to growers. Growers are constrained by their output – they sell all the crops that they can grow on their land and generally face a price for their crop that they cannot influence.

Productivity improvements. Our offering may increase our customer’s productivity. The way our customer realizes the value may be simple. In agriculture, an increase in corn yields directly delivers higher revenues to growers. Growers are constrained by their output – they sell all the crops that they can grow on their land and generally face a price for their crop that they cannot influence.

In many situations, however, increased productivity may deliver value in more than one way. For customers who are capacity constrained, productivity increases revenues, usually net of the additional variable costs required to produce more. For some capacity-constrained customers, greater productivity may help them avoid capital outlays they would have otherwise made to sell more.

For other customers, not selling at the current capacity, productivity improvements may not drive additional revenue. These customers face demand constraints. They could and would produce more without productivity improvements if they had the demand. For these customers, improved productivity provides an opportunity to improve efficiency by reducing energy consumption, reducing labor time, or by redeploying labor to alternative uses. In these cases, productivity is usually more meaningful when expressed as cost savings or costs avoided.

To quantify and dollarize productivity benefits, whether realized as cost reduction, cost avoidance, or revenue increases, the approaches and coaching questions discussed in previous sections are useful.

When there are different ways to realize the value of greater productivity, there are usually distinct value-based customer segments. Teams need to think through the alternative ways that productivity delivers value to identify the best questions to learn which value driver type resonates best. The resulting productivity value drivers are specific to customer types where a few simple discovery questions help in communicating value effectively. Good coaches help their teams organize their thought process, prompting good discovery questions to distinguish between segments, quantifying financial impact for each approach, and making sure teams do not double count the benefits of productivity improvements when many of these benefits are either/or in nature.

Overcome Objections to Quantifying Value. Teams sometimes get stuck quantifying and dollarizing value. Coaches need to help them get moving. Here are some common objections to quantifying value and some coaches’ tips to address them:

-

- We don’t understand our customer’s business math. Perhaps we don’t understand our customers’ business. Good coaches provide the benefit of their experience in helping teams learn more about customers’ operations and financial constraints. Intelligent questions help to move dollarization forward. Preparing intelligent questions in advance of customer conversations boosts the team’s confidence to ask those questions.

-

- Value is hard to quantify because so much of it is intangible. Value drivers that seem less tangible or more difficult to quantify often include revenue value drivers and value drivers based on risk and/or brand. Good coaches help teams overcome their reluctance to quantify ”intangible“ value drivers with creative, disciplined, questions that tease out the business impact of “risk” and “brand” in terms of tangible benefits like durability and reliability or less downtime.

We can’t get good enough data. Scientific standards often set the bar for useful data too high. The data do not have to be perfect. Charles Babbage, the father of modern programmable computers, provided a useful perspective on the question of data quality. “Errors using inadequate data are much less than those using no data at all.” Data quality is a process, not a destination. Customer economic and operating data only need to be good enough to get the customer to start talking about their favorite topic – themselves. Product claims data can be continuously improved based on customer experience and customer conversations. Good coaches get teams to start with hypotheses and refine data over time with customer questions that elicit anecdotes and help to design market research.

We can’t get good enough data. Scientific standards often set the bar for useful data too high. The data do not have to be perfect. Charles Babbage, the father of modern programmable computers, provided a useful perspective on the question of data quality. “Errors using inadequate data are much less than those using no data at all.” Data quality is a process, not a destination. Customer economic and operating data only need to be good enough to get the customer to start talking about their favorite topic – themselves. Product claims data can be continuously improved based on customer experience and customer conversations. Good coaches get teams to start with hypotheses and refine data over time with customer questions that elicit anecdotes and help to design market research.

Coaches provide insights from their experience that build team self-assurance. The challenges of quantifying value are not novel. They are surmounted successfully in many organizations on an ongoing basis. Continuous motivation helps to overcome attitudinal barriers to improved performance.

Great Midfield Play. We understand our customers better when we quantify customer value. With a clear framework and well-articulated features and benefits, our team is equipped to identify and quantify value drivers. Value coaches support teams by providing perspective, practical guidance, and experience, helping even math-phobic team members to organize their thoughts, their questions, their initial calculations, and their follow-up to get better estimates. If we understand how our product is used, it is not that hard to understand how we potentially improve our customers’ business. If we are creative in coming up with initial estimates of what our differentiated benefits are worth, it is not that hard to come up with good questions to refine our basis for estimation.

The result is that good, quantified value content supports value management and value communication. Value management drives strategic decisions aligned with sustainable customer success. Value Propositions provide core sales content to support sales team collaboration with customers by focusing on the business outcomes buyers realize by purchasing our solution. Midfielders see the field and move the ball downfield more effectively, making better passes and setting up shots on goal. More goals, more wins, and more championships are the consequence.

To get the coach’s play card click here.

To learn more about how to quantify value see:

Can Your Sales Team Sell Your Solution’s Value?

To learn more about how sales teams use Value Propositions see:

Value Propositions for B2B Sales Effectiveness

[1]See Stephan Liozu, Dollarizing Differentiation Value, A Practical Guide for the Quantification and the Capture of Customer Value, (Value Innoruption Advisors Publishing, 2016) for additional practical guidance and for perspectives on organizational implementation.