One question is inevitable in any introduction to value based pricing: “What percent of value should we try to capture?” For a product team building their first value model, the question usually arises right after they have set up the math for a few value drivers. Given their efforts, they often anticipate that a single, magic number will get them the rest of the way to setting an optimal price.

We have all finalized a negotiation by splitting the difference. 50% is a natural magic number. But applying strict, share-and-share-alike principles is sometimes unachievable  in practice and may not make strategic sense when feasible. Conditions and circumstances vary. There may be few buyers and few sellers or there may be many buyers, many sellers or both. Products and solutions are positioned differently, whether on a stand-alone basis or within the context of bundled offerings or a broader product portfolio. Value models may be well validated or they may be preliminary estimates with a number of hypotheses yet to be tested. Some customers or customer segments respond to prices and value differently.[1] Competitors in a market react in distinct ways to new products and new pricing strategies. Commercial strategies and sales cultures differ.

in practice and may not make strategic sense when feasible. Conditions and circumstances vary. There may be few buyers and few sellers or there may be many buyers, many sellers or both. Products and solutions are positioned differently, whether on a stand-alone basis or within the context of bundled offerings or a broader product portfolio. Value models may be well validated or they may be preliminary estimates with a number of hypotheses yet to be tested. Some customers or customer segments respond to prices and value differently.[1] Competitors in a market react in distinct ways to new products and new pricing strategies. Commercial strategies and sales cultures differ.

The question of how value should be split arises repeatedly in customer-value-centric organizations. It should be addressed in a thoughtful and systematic way. When building a product development or launch plan, teams debate feasible pricing ranges based on capturing value. Early in the sales cycle, sales teams take any information they have regarding customer-perceived value as they consider initial price quotes. Later in the sales cycle, teams assess how their sponsor might defend a business case to buy, as they plan their chess moves in a price negotiation. In overhauling or refining their commercial strategy, C-suite executives have flashes of insight about how to position customer value in the context of new product launches, key account relationships, service offerings, and new approaches to contracting and negotiation.

The benefits of value modeling, value pricing and value selling are clear enough. The evidence shows that implementing a value based-pricing strategy improves EBITDA by an average of 8%[2] and that the ROI of investing in value based strategies ranges from 130% to 900%.[3] Product teams who incorporate value into their discussions indicate that it helps them understand their positioning better and that it makes their decision-making customer-centric. CRM data from B2B organizations adopting value selling show that opportunities where a Value Proposition is used have 5-15% higher win rates and 5-25% higher price outcomes.

Framing the Question. “What percent of value should we try to capture?” Notice the limitations in how the question is framed:

It is seller-centric, focusing on our It treats the problem as a zero sum game, highlighting the value captured as a percentage of a fixed total value amount or as a slice of a pie. The question, as posed, need not be interpreted as adversarial, but at the very least it is transactional in nature.

It is seller-centric, focusing on our It treats the problem as a zero sum game, highlighting the value captured as a percentage of a fixed total value amount or as a slice of a pie. The question, as posed, need not be interpreted as adversarial, but at the very least it is transactional in nature.- Any single percentage that we discuss is being framed in the context of a static snapshot or image of value. Like any image, the picture quality may be high resolution or it may be fuzzy. Like any image, a snapshot only provides information about the scene that the photographer shot, at the time of its shooting. The objective quality of our value model, and therefore the quality of our snapshots, will improve over time.

Even if we and our customers are considering the same image, we often see different things within the image as important. No matter how good our snapshot, our customers may understand it differently from the way we do.

Even if we and our customers are considering the same image, we often see different things within the image as important. No matter how good our snapshot, our customers may understand it differently from the way we do.

There is more than one way to frame the question, just as there are disciplined, analytical ways to consider how to split value. We start by looking at value splits in the way that most teams do, considering a single transaction, hypothetical or real, in isolation. Then we examine a transactional approach over time, where the notion of a fixed pie to slice is maintained. Finally, we explore a less transactional, more collaborative approach to sharing value that may make sense when the objective size of the pie or the perceived size of the pie is variable and when the relationship between buyer and seller comes into stronger focus, evolving over time.

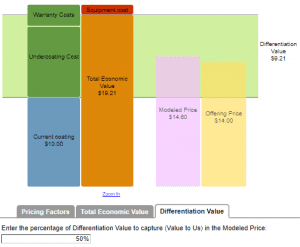

Transactional Snapshot. At a specific point in time, for a specific circumstance, there are a number of factors to consider as we target the percent of value we should try to capture. Before looking at some of these factors for splitting customer value as measured, it is worth evaluating a few aspects of measured value itself.

- Consider the objective quality of value as measured. How reasonable are our estimates? How defensible are our claims? How much variability do we anticipate among customers in the applicability of our estimates and the realizability of our claims? If we keep talking about value with customers, the quality of our estimates will improve but we will use the information we have now to make decisions today. An honest assessment of the quality of value content helps to use that content appropriately at any point in time.

- What is included in the value model? Some value models do a more thorough job than others in quantifying value drivers. If “intangible” risk and cost value drivers are left unquantified, then these are clearly factors in thinking about value capture. Alternatively, if the objective benefits of intangible value drivers have been teased out and quantified appropriately, the list of pricing factors for splitting value is likely to be shorter.

- How are customer perceptions likely to differ from our best assessment of objective value? What do we plan to do to change customer perceptions, through marketing content and by delivering sales messages to customers that change their thinking?

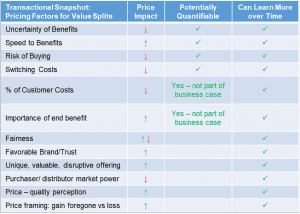

Let’s consider a number of pricing factors compiled and combined  from several sources. Nagle and Müller in The Strategy and Tactics of Pricing[4] highlight six price sensitivity factors that are mostly psychological. Earlier editions[5] of The Strategy and Tactics of Pricing point to a few other factors as well. Stephan Liozu in Dollarizing Differentiation Value[6] provides an in-depth, practical discussion of setting prices based on the value pool, providing a comprehensive list of factors. Joanne Smith has written and presented extensively on value splitting as well.

from several sources. Nagle and Müller in The Strategy and Tactics of Pricing[4] highlight six price sensitivity factors that are mostly psychological. Earlier editions[5] of The Strategy and Tactics of Pricing point to a few other factors as well. Stephan Liozu in Dollarizing Differentiation Value[6] provides an in-depth, practical discussion of setting prices based on the value pool, providing a comprehensive list of factors. Joanne Smith has written and presented extensively on value splitting as well.

A list of factors is shown in the table, together with their  directional impact on both price and the value we would capture. Some of these factors could be phrased in the negative in which case the price impact directions would reverse. The factors shown are an interesting mix. All of them are potentially psychological to buyer stakeholders, but then so are quantified value drivers. Messaging to address price factors and messaging for value drivers should both be attuned to behavioral and irrational customer responses as well as well as to the available math.

directional impact on both price and the value we would capture. Some of these factors could be phrased in the negative in which case the price impact directions would reverse. The factors shown are an interesting mix. All of them are potentially psychological to buyer stakeholders, but then so are quantified value drivers. Messaging to address price factors and messaging for value drivers should both be attuned to behavioral and irrational customer responses as well as well as to the available math.

In any situation, only some of these factors will be applicable. Product teams identify which factors are important, assessing their relative importance as they apply either formulae or judgment to come up with a reasonable value split or range of value splits as they consider pricing decisions.

If some of these factors are included in a value split discussion, they have probably not been accounted for in the direct value quantification so far. As highlighted in the table, several of these factors are potentially quantifiable. Other factors are quantifiable as well, not that they would directly feed the customer’s business case to buy, but these quantified factors could be useful as qualifying and segmenting factors. As also highlighted in the table, our mathematical and psychological understanding of all these factors, just like our understanding of our value drivers, is subject to learning over time. Practical experience in specific deal situations, customer interviews, case studies, market research, and A/B testing can potentially be brought to bear to understand the importance and impact of relevant factors in a given marketplace.

In any value pricing discussion, the aim is to reach a sensible initial or final decision for proposed prices based on what we know today. Considering pricing factors as part of a value split discussion, considering “what ifs” to account for risks, and using conservative hypotheses for uncertain costs are reasonable approaches to understanding the business case to buy for a specific customer in light of a proposed price.

Strategy and the Transactional Movie. Movies may be  composed of single-frame snapshots, but they are more than the sum of their parts because these snapshot unfold over time in sequence. A sequence can be more panoramic and can be reframed and refocused to provide more information than individual images, while considering the dynamic nature of a series of individual transactions.

composed of single-frame snapshots, but they are more than the sum of their parts because these snapshot unfold over time in sequence. A sequence can be more panoramic and can be reframed and refocused to provide more information than individual images, while considering the dynamic nature of a series of individual transactions.

Good strategy plans for market successes and failures over time. Good strategy invariably utilizes multiple snapshots as scenarios that help teams build their go-to-market plan or their annual business plan. Considering strategy from a transactional perspective, the question changes somewhat. “What policies should we put in place and what action steps should we take so that we capture meaningful value over time?” Pricing factors that are relevant in snapshots remain relevant in a transactional movie. As we continue to focus on our portion of a fixed pie, sliced a deal at a time, these factors help formulate a consistent approach to splitting value. But some new elements are brought to bear when strategic planning is applied to an unfolding, dynamic story. These include:

- Statistical Estimates: Understanding How Customers May React.[7] Demand elasticities and conjoint analyses have greater statistical relevance when we are considering multiple transactions over time. Whether or not sampling and statistical estimates were based on objective value as quantified in our value model and whether or not sales and marketing are ultimately successful in aligning customer perceived value with value as quantified, these estimates supplement our judgment. They provide information about price sensitivity that helps us to assess: (i) What if we get our value wrong? (ii) How should we adjust prices if we are wrong? and (iii) how should we reasonably expect customers to react as we adjust?

- Cost, Production and Profitability Information. Cost and production information are potentially relevant to individual transactions but they are certainly required in any broader, multi-transaction strategic discussion. We need to assess the profitability implications of our pricing framework for a product, given our costs. We need to align our pricing strategy with production constraints. If we are launching a product where production will come on-line slowly or where we are expecting logistics or service bottlenecks, we might consider high initial pricing consistent with our ability to deliver and install our product or solution on a timely basis.

- Segmentation and Offer Design Strategy. Individual transactions, taken together for different customers or customer conditions, help us to identify value-based segments and different approaches to offerings based both on these segments and on our broader product portfolio and capabilities. Value to customer becomes a way to think about the business case to buy specific offerings, based on rational (and irrational) customer decision-making, a segment at a time. A consistent approach to splitting value across segments, given costs, helps to keep pricing consistent and perceived as fair by customers over time.

- Marketing Strategy, Sales Enablement and Post-Sale Implementation. Having strong differentiated value, as objectively measured, is an advantage, but if customers don’t understand it and recognize it in their buying decisions, we will never be able to capture a meaningful portion of our value. If customers don’t realize anticipated value in practice, they will switch to competitors in their next purchasing decision. Marketing content and objectively defensible value should be strongly aligned. Sales teams need the tools and training to have customer conversations that improve customer awareness of our differentiated value and that build our value into customers’ internal business cases to buy. Implementation programs should be consistent with, and target the attainment of, a customer’s expectation of value. Capturing value with price requires customer value realization, both pre-sale and post-sale.

- Judgment and Scenario Planning to Assess Competitor Reaction. As we consider our pricing strategy on a dynamic basis, we need to assess likely competitor reaction, especially those competitors that are the most likely reference points for our customers. It usually takes judgment and an understanding of a competitor’s business to gauge their likely responses. Considering these competitor reactions as scenarios in terms of value created for the customer provides perspective on our pricing strategy and helps to plan our own potential responses.

All of these elements go into a Pricing Strategy based on value. The Strategy and Tactics of Pricing[8] examines pricing strategy in depth, organizing the primary strategic choices into three approaches: skim, neutral and penetrate. A pricing strategy should be aligned with, and formed by, both pricing factors and the strategic elements above. Supply considerations may argue for launching a product with a skimming strategy. Rapid competitor innovation to match our differentiation often argues for a penetration strategy. Barriers to entry and a uniquely differentiated product may facilitate reasonable value capture with fast market share growth based on a neutral pricing strategy. Maximizing lifetime product value, when faced with organizational sales and marketing challenges, sometimes suggests penetrating the market with lower value capture.

To execute on our pricing strategy, we need a consistent approach to initial pricing of multiple offerings sold to multiple segments and a consistent approach to how we respond to customer and competitor reactions. Designing a pricing approach, based on feasible but consistent value capture, helps to build sales confidence in how they propose and defend pricing proposals. This drives sustainable profitability.

The Collaborative Movie. The chapter on value splitting in Anderson, Kumar and Narus’ Value Merchants[9] has a title that reflects a different perspective on customer relationships  from that articulated so far. Chapter 7 is entitled “Profit from Value Provided: Earning an Equitable Return.” Framing the question in terms of “equity for both parties,” rather than “the % of value that we capture,” reflects a different posture. It suggests centering the conversation on a dual focus on both buyer and seller. This is less a transactional approach and more a collaborative approach to value. It invariably makes sense over a strategic horizon, so we will ignore static, single-deal snapshots as we consider the movie.

from that articulated so far. Chapter 7 is entitled “Profit from Value Provided: Earning an Equitable Return.” Framing the question in terms of “equity for both parties,” rather than “the % of value that we capture,” reflects a different posture. It suggests centering the conversation on a dual focus on both buyer and seller. This is less a transactional approach and more a collaborative approach to value. It invariably makes sense over a strategic horizon, so we will ignore static, single-deal snapshots as we consider the movie.

A few elements of customer conversations are indicative of a collaborative approach to value pricing. Transparent discussions, between buyer and seller, of value shared is a powerful sign. Use of the word “fair” by both buyers and sellers is another indicator. Direct discussions of differences in perceptions between buyer and seller of the size of the pie is an honest precursor to collaboration. An openness on both sides of the table to consider the evidence to get to a shared vision of value is a good attitudinal sign that sustainable collaboration is possible. Direct discussions of accountability and deliverables both by buyer and by seller indicates that we are on our way to a collaborative approach.

Philosophically, collaboration sounds great, but it does not necessarily make hard-headed business sense. Collaboration takes time and energy both by buyer and seller. Here are a few identifiable conditions that, taken in combination, point in the direction of a collaborative approach:

- If there are few buyers and few sellers, then both buyer and seller have good reason to collaborate.

- If there are important end benefits (or losses avoided) to a buyer of making a purchase, then the buyer has a good reason to collaborate.

- If an offering is unique, then the buyer has reason to collaborate.

- If the seller provides continuing innovation over time, then the buyer has reason to collaborate.

- If the buyer has significant market power or if the buyer represents a strong alpha or beta customer, then there is a good reason for the seller to collaborate.

- If there are significant risks or significant costs of switching, including required investment, then purchasing decisions tend to be sticky and long-standing. The large cost of change gives the buyer a clear rationale to demand seller collaborative commitment as a condition for purchase. The eventual stickiness of a decision provides the seller with a good reason to put in time and energy to collaborate with the buyer upfront to get returns over time.

- If the size of the value pie is not fixed, then there is a good reason for both buyer and seller to cooperate to increase its size.

- If there are significant risks of outcomes to be realized and if deliverables are required both from buyer and seller to minimize these risks and to maximize results, then both parties have a strong reason to collaborate.

A collaborative approach is only achievable when sales teams build relationships of trust with buyer sponsors and stakeholders. Thus collaborative approaches to value pricing are only possible with sales management buy-in and when sales teams develop the relevant skill set for collaborative customer conversations.

Even if a market dynamic suggests a collaborative approach to value based pricing, not all customer sponsors and customer stakeholders enter naturally into collaborative relationships with vendors. Procurement rules sometimes get in the way. If value discussions only begin after we have received an RFP, a collaborative approach to value pricing is less likely to be feasible. Dysfunctional, uncollaborative cultures within buyer organizations can also be a barrier.

A collaborative approach to value pricing is almost always a precondition for risk-sharing or value-sharing contracts, but value based contracting is not required for collaborative value pricing. When outcomes are hard to measure, value-sharing contracts do not make sense. When attributing success and failure to buyer deliverables and seller deliverables is difficult, then the moral hazard problem makes risk-sharing and value-sharing more challenging and potentially inadvisable.

A collaborative approach, strategically and in customer relationships, promotes pricing sustainability and business predictability. It starts to eliminate the list of pricing factors from each purchasing decision, shortening the price discussion and negotiation process to focusing on what is fair and consistent.

Value Based Decision-Making, Pricing and Selling. All great organizations are customer-centric. Innovative businesses benefit by making their product and pricing decisions based on  customer value. Value brings the customer’s business into focus and highlights our differentiation. Quantified value shines a spotlight on the business pain points we address and on what we deliver.

customer value. Value brings the customer’s business into focus and highlights our differentiation. Quantified value shines a spotlight on the business pain points we address and on what we deliver.

Incorporating value into pricing decisions and pricing strategy improves product launch success and business performance, whether taking a transactional approach or a collaborative approach. Elevating value-centric customer conversations into a collaborative approach, where possible and advisable, makes our pricing strategy and our commercial strategy more predictably profitable.

Learn more about value maps as a tool and as a way to start value based pricing:

Value Maps for Customer-Centric Product Strategy

For more information on quantifying financial value, read:

Can Your Sales Team Sell Your Solution’s Value? Can You?

[1] See Thomas T. Nagle and Georg Müller, The Strategy and Tactics of Pricing, A Guide to Growing More Profitably (Routledge, 6th edition, 2018), pp. 47-54 for a discussion of value based segmentation and pp. 118-125 for a discussion of buyer types.

[2] See John Hogan, “Building a World-Class Pricing Capability: Where Does Your Company Stack Up?” Monitor Group Perspectives, 2008.

[3] See Stephan Liozu and Andreas Hinterhuber, eds., The RoI of Pricing, Measuring the Impact and Making the Business Case (Routledge, 2014), especially the chapter by Stephan Liozu, “RoI and the impact of pricing: the state of the profession.”

[4] See Thomas T. Nagle and Georg Müller, The Strategy and Tactics of Pricing, A Guide to Growing More Profitably (Routledge, 6th edition, 2018), p. 147.

[5] See Thomas T. Nagle, John E. Hogan & Joseph Zale, The Strategy and Tactics of Pricing, A Guide to Growing More Profitably (Prentice Hall, 5th edition, 2011), pp. 132-133.

[6] See Stephan Liozu, Dollarizing Differentiation Value, A Practical Guide for the Quantification and the Capture of Customer Value in B2B Markets, (Value Innoruption Advisors Publishing, 2016), Chapter 7, “Understand the Value Pool and Setting Prices (Steps 5 and 6).”

[7] For a more extensive discussion of statistical estimates in the context of value pricing, see Thomas T. Nagle and Georg Müller, The Strategy and Tactics of Pricing, A Guide to Growing More Profitably (Routledge, 6th edition, 2018), Chapter 8, “Measurement of Price Sensitivity, Research Techniques to Supplement Judgment.”

[8] See Thomas T. Nagle and Georg Müller, The Strategy and Tactics of Pricing, A Guide to Growing More Profitably (Routledge, 6th edition, 2018), p. 137-142.

[9] See James C. Anderson, Nirmalya Kumar and James A. Narus, Value Merchants, Demonstrating and Documenting Superior Value in Business Markets, (Harvard Business School Press, 2007), Chapter 7.