For B2B companies with big ticket, innovative solutions, selling to the C-suite can become organizational mom and apple pie. It isn’t surprising. All it takes is a single sales success story.

For innovative products or solutions with significant customer impact, the go-to-market problem is invariably a long and complex sales cycle. Customer middle management contacts frequently control the buying process and impede broader enterprise engagement. A talented sales rep who finds his or her way into a good C-suite conversation can kick start a buying process and generate organizational urgency. When the big deal closes, sales management, looking to replicate success, concludes that C-suite targeting is the answer.

For innovative products or solutions with significant customer impact, the go-to-market problem is invariably a long and complex sales cycle. Customer middle management contacts frequently control the buying process and impede broader enterprise engagement. A talented sales rep who finds his or her way into a good C-suite conversation can kick start a buying process and generate organizational urgency. When the big deal closes, sales management, looking to replicate success, concludes that C-suite targeting is the answer.

Selling to the C-Suite is easy to say, hard to do, and even harder to scale. For complex B2B products or solutions the degree of difficulty rises.

The big meeting, with the C-suite in the room, rarely delivers results without including the right team members. Must-haves often include the relevant technical expertise and a capability to credibly communicate other customer experiences and successes. In B2B, consensus buying is the exception rather than the rule. While the executive may be the primary target, there are likely to be supporting players with diverse interests on the other side of the table. Going into these meetings without pre-sales, sales engineers, product management or subject matter experts is suicide. Sales is a team sport and team preparation is essential.

That said, not all C-suite opportunities are planned. CEO’s, COO’s and CFO’s like to drop into meetings unannounced. And a good rep playing in the right traffic may create chances for random encounters. Sales readiness for those C-suite opportunities can improve sales performance.

To prepare for planned and unplanned C-suite sales conversations, it is important to understand your audience.

The C-Suite. Who are you calling on?

We all start with stereotypes but every personality in the C-Suite is different. Those differences mean that sales has to do its homework. Sales needs to understand the executive’s background and experience to identify messages that will resonate, natural directions for a conversation and likely questions or concerns.

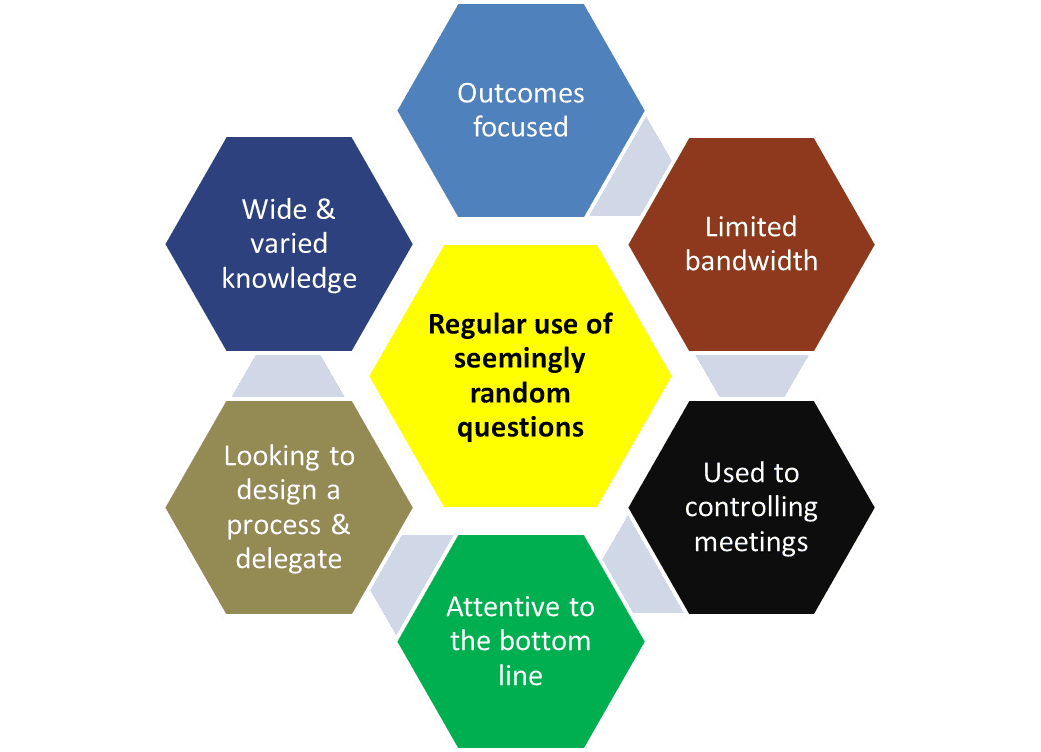

As someone who called on executives selling complex financial transactions for 12 years and then as someone who listened to any number of vendor pitches as a CFO, COO and CEO for 18 years, it is tempting to dwell on the specifics of every war story. Yet despite individual differences, there are some remarkable similarities among executives, between high level meetings and across C-suites. Some C-suite behaviors are culturally inbred. Some C-suite behaviors are habit-forming. It is useful to try to isolate some common characteristics that can reasonably be expected in C-suite conversations:

Results focused. Executives are accountable for outcomes. They naturally want employees, consultants and vendors to deliver results and are bound to ask about them. Outcomes questions are a way to do due diligence, to begin a negotiation, to size up a vendor’s experience and to force vendors to set explicit expectations for which they can be held accountable.

Results focused. Executives are accountable for outcomes. They naturally want employees, consultants and vendors to deliver results and are bound to ask about them. Outcomes questions are a way to do due diligence, to begin a negotiation, to size up a vendor’s experience and to force vendors to set explicit expectations for which they can be held accountable.- Limited bandwidth. The scarcest resource for most executives is time. Every 15 minutes they save in a vendor meeting is found money. No matter how great your product, no matter how spellbinding your presentation, executives care about return on time spent and are unlikely to give vendor presenters as much time or attentiveness as they believe they deserve.

- Meeting control. For anyone who routinely sits at the head of the table, it is second nature to take control of a meeting, sometimes aggressively and sometimes to the point where the executive doesn’t realize that he or she is the alpha dog. If the executive isn’t saying anything, something is wrong. If the executive is engaged, make sure you get their buy-in on agenda and timing. Expect them to control the conversation.

- Attentive to the bottom line. Remember that even executives aren’t omnipotent. Shareholders assess their company’s financial performance in the stock market every day. C-suites report to boards of directors who hire and fire them on the basis of financial results. They spend large amounts of time wearing flak jackets in their conversations with the Street, persuading analysts and investors that they will deliver a better bottom line. They prepare themselves to articulate the connection between every major operating initiative and a financial deliverable. They expect a vendor to do the same by highlighting a bottom line impact on their business.

- Designing a process and delegating. There is a direct relationship between limited executive bandwidth and how they actually do spend their time. They want to get to a decision as fast as possible. Unless you are really lucky, that speed is unlikely to mean impulse buying or making a purchase on inspiration. The easiest way an executive can make a decision and move to the next crisis of the day is to make a decision about a process and to delegate next steps to one or more members of the buyer’s team. That point of any meeting is often a momentary opportunity to get executive buy-in on hurdles and timetable in a buying process. Seizing that moment is why you wanted the meeting to begin with.

- Wide and varied interests. One reason that executives limit the bandwidth they have available for routine meetings and processes is that they consistently preserve bandwidth to identify opportunities and drive new initiatives. The only way a member of the C-suite can continue to push others and prompt them with out-of-the-box ideas is to maintain a disciplined curiosity. Executives are often voracious readers. The subject matter of their most recent interest is often random. They use conversations with many counterparts to feed their curiosity. You never know the last book they have read, the last blog post that caught their attention, or the last horror story they have heard from a board member, a banker or an employee.

All of this means that you have to expect the regular use of seemingly random questions. As a CEO, the biggest employee complaint I get is that I don’t give my employees enough warning. I ask too many unanticipated questions. It put my team off balance. To me it’s an acquired habit I couldn’t break if I wanted to. But I don’t really want to break the habit because it helps me control meetings and it helps me figure out who has done their homework. Sales teams have to be prepared to respond to executive randomness and unexpected questions. The best sales teams, by preparing key messages, can exploit unexpected questions by guiding them to critical bottom-line answers.

In my next blog, I will look at the concrete steps you can take to prepare for a C-suite meeting or encounter, but the objectives given your audience should be clear:

- Design a crisp yet flexible agenda and content. You may be drawn into a conversation about why you are better and the outcomes your solution provides at any point in the meeting.

- Be ready to articulate your value proposition. The quantified customer value your solution provides is the only answer to the bottom line question.

- Plan for random questions from different people in the room. Plan to answer the executive’s questions crisply and simply. Plan for polite and engaging ways to deflect questions from others that require complex answers to follow-up actions and smaller meetings.

A shared value proposition is a powerful and often necessary weapon for sales teams to deploy in C-suite conversations as well as elsewhere in the sales cycle. Selling to the C-suite works, but only if you keep continued focus on your audience, their objectives and anticipate their behavior.