Until smartphones and mobile devices appeared, the list of Universal Tools was pretty short. A Swiss army knife was always near the top. When I was a kid I saved up and bought the only kind of Swiss army knife you could get back then. It was red with a white cross; it had five tools. It was handy, compact and did anything in the woods that you needed it to do.

Until smartphones and mobile devices appeared, the list of Universal Tools was pretty short. A Swiss army knife was always near the top. When I was a kid I saved up and bought the only kind of Swiss army knife you could get back then. It was red with a white cross; it had five tools. It was handy, compact and did anything in the woods that you needed it to do.

Swiss army knives come in other colors now. What’s more, you can get a Swiss army knife with 87 tools and 141 functions. For only two grand. If you’re lucky, it comes with a user-manual-smart-phone-app and pants with triple stitched pockets.

Sometimes it’s more efficient to keep your tools simple and to use them well.

For some B2B companies, Economic Value Estimation® (EVE®) is a universal tool. EVE can be used in product planning and decision-making to work through a product concept, design the product, make go-no go development decisions, set a product price, devise an approach to market segmentation and design offering and bundling strategies. EVE can be used in marketing and sales execution to generate strong marketing collateral and to provide pre-sales and sales teams with tailored value propositions, enabling them to have better customer conversations, close more deals and realize higher prices.

That’s a lot for one tool to do. Thanks to Tom Nagle and his co-authors through five editions of The Strategy and Tactics of Pricing, EVE is a strong common framework for understanding, applying and communicating customer economic value. And thanks to many others who have used and/or published similar methods with similar names and labels (see especially James Anderson et. al.’s Value Merchants), there is extensive know-how available to help companies deploy value strategies in practice.

EVE is used to accomplish many objectives. Undoubtedly this is because EVE makes B2B customers and their measurable goals the focal point of any discussion. As a framework for customer value, it focuses B2B teams on product differentiation; differentiation translates into higher margins. Finally EVE is a solution for companies who realize that their customers do the math when they make purchasing decisions, whether their vendors help them or not.

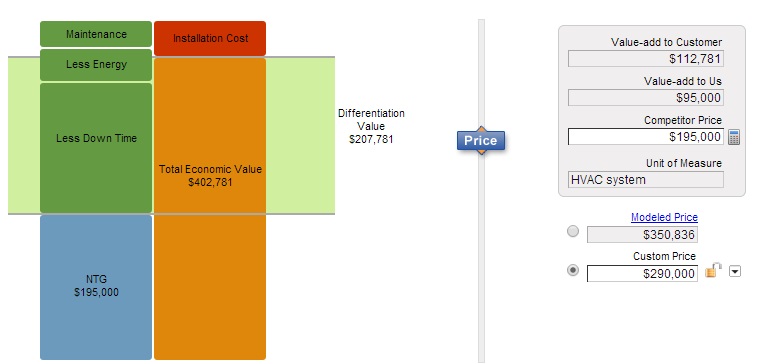

As a framework, EVE is clear and intuitive. Starting with a product’s differentiated features and benefits, the EVE value modeling process generates quantified value drivers, each of which makes a direct economic comparison between two products. Value drivers are comparative. A value driver is expressed in the form of a difference or the impact of choosing one product over the other. In the same EVE graph as value drivers are individual Prices. A Price provides information about one of the two products being compared in EVE, a competitive reference product and your product. By design, value drivers are stacked in the same graph as Prices to build a waterfall that gets from the price of a competitor product to the price of your product and the all-important result of Customer Value. The EVE framework in this form was designed for making decisions about offerings, pricing and price setting.

As a framework, EVE is clear and intuitive. Starting with a product’s differentiated features and benefits, the EVE value modeling process generates quantified value drivers, each of which makes a direct economic comparison between two products. Value drivers are comparative. A value driver is expressed in the form of a difference or the impact of choosing one product over the other. In the same EVE graph as value drivers are individual Prices. A Price provides information about one of the two products being compared in EVE, a competitive reference product and your product. By design, value drivers are stacked in the same graph as Prices to build a waterfall that gets from the price of a competitor product to the price of your product and the all-important result of Customer Value. The EVE framework in this form was designed for making decisions about offerings, pricing and price setting.

EVE is one of several methods for quantifying and communicating value to a customer making a purchasing decision. Alternative approaches include TCO and ROI. Used carefully, they all get to the same answer. But there are differences in emphasis and in practice, resulting in strengths and challenges of each. One useful reference point for comparing methods is to think in terms of customer math, some first principles and a few common-sense practices.

EVE is applied to so many different problems that sometimes the method needs to be stretched in unexpected ways. Thought and care in these situations can help maintain clarity. With the right attention, EVE provides a strong foundation for good decisions and powerful value propositions.

EVE Strengths

As a practical method, EVE has four essential strengths:

- EVE focuses on differentiation. Marketers and product managers are naturally drawn to EVE. The framework starts by identifying your product’s differentiated features and articulates why they should matter by recognizing the resulting customer benefits. Differentiated features and benefits are important points that good marketers are eager to describe clearly. Value drivers convey what your differentiation is worth directly to your customer, expressed comparatively as an impact or a difference. A value driver quantifies the improvement in cash flow or increase in profitability your customer realizes by choosing your product over the competitor. Value drivers are the natural quantitative extension of qualitative marketing messages about product differentiation.

- By nature, EVE’s broad scope helps articulate what is important to the customer. The language of EVE is one of its strong suits. As a method, it encourages teams to look broadly for all sources of value, not just at cost efficiencies. EVE elevates the business conversation by helping to identify what is important to the customer.

Too many B2B value propositions look at customers through the narrow lense of how a product reduces obvious operating costs. Saving labor, reducing maintenance and other operating efficiencies may be the clearest and simplest value messages to quantify. These messages often resonate best with an operating sponsor at a B2B customer. But differentiated products often have the potential to increase a customer’s revenue and reduce a customer’s risk as well. C-level executives care about revenue and risk. Even if your sponsor is best equipped or most incentivized to respond to cost reduction, both you and your sponsor need to be armed and dangerous in persuading their C-suite to buy your product.

A good EVE-based value proposition considers revenues and business problems not usually included in operating costs like the risk of low probability but significant events. Demonstrating how your product increases a customer’s revenue or reduces their risk of litigation or risk of regulatory action adds quantitatively to product value and adds qualitative impact to value propositions. These value messages may resonate better with some stakeholders at a customer than with others, but a dialog about what is important to your customer helps to set a better tone for the conversation and helps to differentiate you and your offering. - EVE focuses on the relevant decision, providing a clear bottom-line answer. EVE sets up a simple assessment: it provides a direct numerical comparison of your product to a single competitor. If you have identified the right competitor, the customer discussion couldn’t be more direct or more relevant. The Value to Customer is a single number that quantifies how much better your product is than the competitor. If the messages are clear, there is limited potential for customer confusion about what question an EVE-based value proposition is trying to answer. “Our product is more valuable to you than Brand X by $300,000 per annum.”

A clear direct value statement or value hypothesis can be a strong starting point for discovery. Even if you haven’t identified the right competitor, you stand a good chance of learning more about your competitive situation by using an EVE comparison in sales planning as a basis for dialog.

For some customer decisions, incorporating timing considerations provides a natural extension of the customer conversation about purchasing durable products or entering into a long-term contract. In a multiyear framework, Value to Customer year by year is the right input to a financial analysis of the relevant decision. - EVE is efficient with information. EVE provides only the information that is needed to make a rational decision and no more. It doesn’t set out to provide a complete or total analysis of the customer’s business, but instead sticks to an analysis of the cash flow or profitability impact of your product relative to a competitor. It is focused on a comparison of two products and includes no superfluous data beyond what is needed for that quantitative comparison.

Irrelevant information about a customer’s business in a customer discussion is risky; customers usually know more about their business than you do. Irrelevant information invites discussion and debate that have nothing to do with your key messages and that have nothing to do with a customer’s decision for or against your product. Avoiding tangential discussions and avoiding irrelevant challenges keeps customer conversations from getting stuck in the mud.

EVE Challenges

There are some aspects of EVE analysis that present challenges in implementing a value strategy. Sometimes these challenges are part of the universal tool problem as product teams make the transition from product launch decision-making to sales and marketing execution. With clear thinking, potential pitfalls can be avoided. But getting it right takes care and attention. It is worth asking three questions that help identify and address the challenges of implementing EVE:

- Have you planned your value communication for different competitive situations? Practitioners of EVE often encourage a focus on a single next best competitive alternative, at least for a given customer segment. Laser-like focus on a single competitor is good when you are trying to get quantified estimates of value into shape. Focus on the best single competitor makes sense when you are making decisions; setting a price to beat a weak competitor is usually a recipe for commercial disaster.

But the commercial reality of deploying value propositions in execution often presents a variety of competitive situations. Customers may consider competitors other than the one you identified as the next best alternative for several reasons. A customer may not have the same information about competitors, sometimes because of competitor marketing messages and sometimes because customer research is incomplete. A customer’s pre-existing vendor relationships may also drive which competitors get a seat at the table in any beauty parade. A customer’s CFO may be asking why spend any money at all, in which case the relevant competitive reference point for the CFO conversation is not a direct competing product for purchase, but is instead the status quo or the way your customer is doing things today. As a result, a value proposition, to be useful in customer dialogs, generally needs to be prepared against more than one competitor. This preparation is no different in character from a multiproduct TCO comparison. But it is an important additional step to take in preparing value propositions for sales execution. - Is your unit of measure clear? In starting an EVE analysis, there is sometimes an early step that is not made clearly enough. In framing the discussion, product teams decide either explicitly or implicitly on the underlying unit in which they express their value drivers and prices, whether it is per pound of product, per unit of output or per year. This is what we mean by unit of measure. Having a common, consistent unit of measure for all value drivers and prices is necessary to provide a clean graphical display of a value proposition. Having a common unit of measure for value drivers and prices is essential to generating a meaningful customer number by adding up value drivers, net of price differentials to calculate Value to Customer. Unless the unit of measure is consistent within a value proposition, the bottomline answer will be meaningless and the graph will be gobbledygook.

Being clear about your unit of measure is not rocket science. Often it helps to choose an initial unit of measure that will resonate with a customer, like a key customer metric or KPI. For example, if your customer is producing something or performing a procedure using your good, then a useful unit of measure is “per unit of customer output” or “per procedure.” Using a customer metric or KPI is useful in conversations with an operating manager. Alternatively, in other circumstances, choosing a time period as a unit of measure can be helpful, for example “per year” or “per life of the contract” or “per life of the equipment.” Using a time period helps in expressing the financial impacts of your product that matter in the C-suite. Using a time period as a unit of measure also helps in a multi-period value proposition when timing is important in your customer’s decision.

Once you have been clear about the unit in which to build and calculate a value driver or a price, translating the answer into other units is straightforward for communication purposes. Unit conversions are invariably simple multiplication or division. A standard healthcare example is to translate the value of a product (drug or device) per procedure into the value of the product per hospital per year by multiplying the first number by hospital procedures per year. Clear unit choices mean clear unit translations. - Are you clear in the way you quantify value that arises from product acquisition efficiencies? One universal tool challenge of implementing EVE arises when a B2B product is differentiated in a way that results in different amounts being purchased of the two products under comparison. For chemicals or ingredients producers, their differentiated product may be more efficient per pound or per litre in their customer’s production process or recipe. A more efficient hospital device or diagnostic or a more reliable building product may result in efficiencies by reducing the need of a B2B customer to purchase as much product over time. For durable equipment producers, acquisition efficiencies sometimes occur when one system or machine is more productive than its competitor. In all of these circumstances, there may be a source of value resulting in different amounts purchased of the two products being compared.

Differentiation of this type is a source of customer value. There is an efficiency providing a customer benefit that happens to be realized by purchasing fewer units of your product than of the competitor’s product. For users of EVE, it is natural and reasonable to build a value driver for this sort of efficiency. After all, a more efficient or more productive product may provide a powerful quantified value message. This sort of product acquisition efficiency value driver is potentially different from other value drivers and might usefully be labelled an “Acquisition Efficiency Value Driver.”

Accurately measuring the economic benefit of an Acquisition Efficiency Value Driver to a customer involves the use of Prices of the two goods being compared. Consequently, the graphical layout of an EVE value proposition where Prices are shown separately from value drivers needs to be thought through and applied in a way that best suits the goals and objectives of the tool. When Acquisition Efficiencies are involved, it is a good idea to: (1) be clear about customer purchasing behavior assumptions, (2) start with a unit of measure that aligns with a customer metric or time period, not a unit of measure based on the units of product to be purchased and (3) choose an approach to displaying and calculating value drivers and Prices that is clear and avoids double counting of acquisition efficiencies.

In sum, EVE is an incredibly versatile and useful tool. It focuses on the essential information for making a product comparison. But good EVE results need to pay attention to: (1) whether you are using the tool for decision-making or for execution, (2) the unit of measure for value drivers and prices, and (3) whether a source of value or differentiation is directly reflected in customer outlay on the alternatives being compared.

Organizations looking to make customer math central to their approach to product management, marketing and sales almost always start with spreadsheets. But dueling spreadsheets can cause confusion. Spreadsheets don’t usually provide a common framework. They don’t embed the disciplines that avoid mistakes. They don’t build fluency in a common language understandable by the customer.

To embed the customer math of differentiation in your organization, you need a scalable platform with the following features and benefits:

- A clear framework to make comparisons in your customer’s language

- Designed to articulate the primary ways your product is better

- Easy to follow

- Easy to use

- With disciplines that help avoid mistakes

- Easy to change units of measure to translate value effectively for different stakeholders

- Consistent graphics and messages that correspond to product differentiation

- Customized but QA’ed materials to leave behind

A scalable cloud platform drives good decisions and effective, tailored customer value propositions that highlight differentiation, enhance decision-making and improve value capture.

About the Author:

Peyton Marshall is CEO of LeveragePoint. Previously, he served as CFO and Acting CEO at Panacos Pharmaceuticals, Inc., CFO of EPIX Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and as CFO of The Medicines Company through their initial public offering and the commercial launch of Angiomax®. Previously, he was an investment banker in London at Union Bank of Switzerland, and at Goldman Sachs where he was head of European product development. He has served on the faculty in the Economics Department at Vanderbilt University. Dr. Marshall holds an AB in Economics from Davidson College and a PhD in Economics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.